4 Best Intermittent Fasting Frequency, Timing, & Duration from Beginners to Pro Level!

In recent years, intermittent fasting (IF) has garnered increasing attention as a strategy for achieving weight loss, enhancing overall health, and promoting longevity. However, given the multitude of fasting methods available, it can be challenging to know the Optimal Intermittent Fasting frequency at which to engage in fasting practices. This article will examine the recommended frequency of intermittent fasting and Intermittent Fasting duration (IF) for each respective type.

Table of Contents

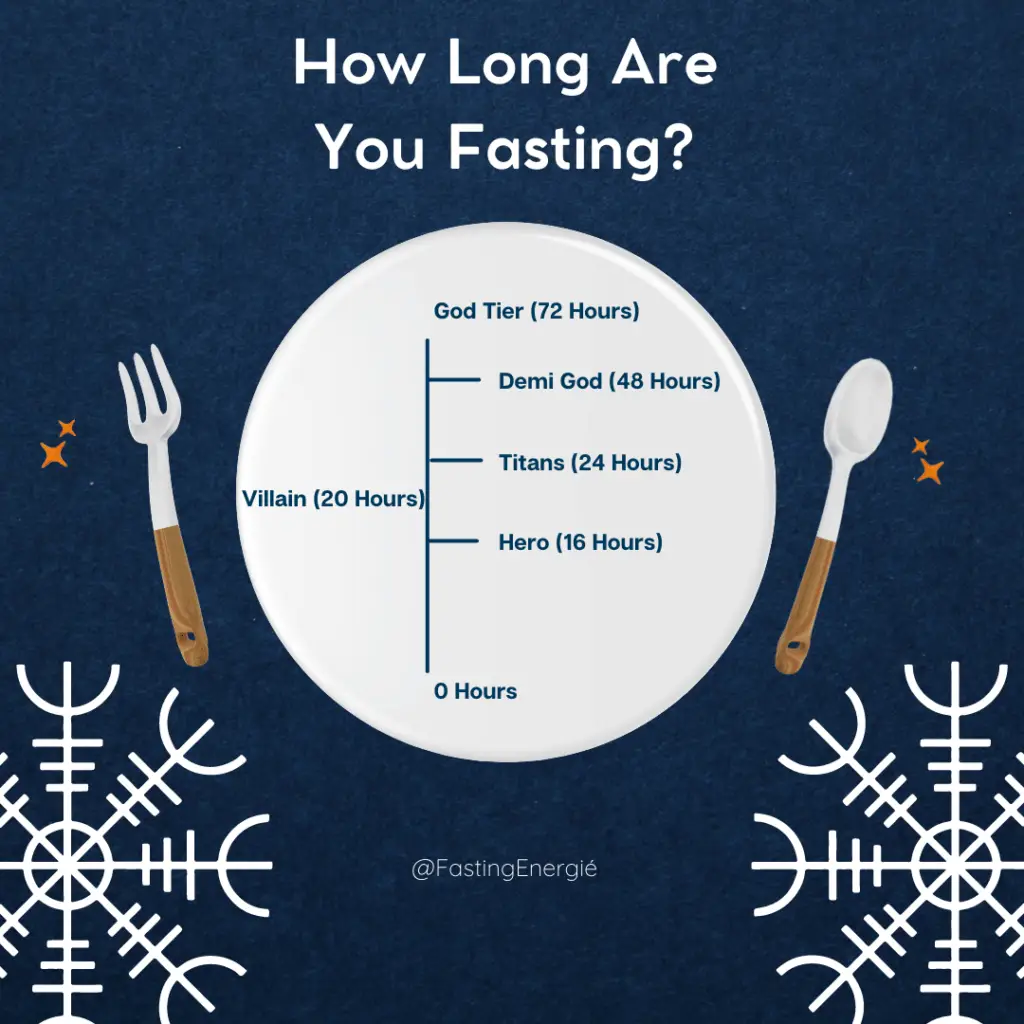

Best intermittent Fasting frequency, timing & duration!

1. Understanding Intermittent Fasting:

Intermittent fasting (IF) is not a diet, but rather an eating pattern that alternates between eating and fasting periods. IF, from a physiological standpoint, taps into our body’s innate capabilities for energy storage and utilisation, which can have repercussions for metabolism, hormone balance, and cellular functions.

Short-term fasts, for example, have the most impact on metabolic rate and insulin sensitivity, whereas extended fasts can have an impact on cell repair processes and hormone synthesis.

2. Starting as a Beginner: Testing the Waters:

2.1. Initial Physiological Responses

When a newbie begins with IF, the body goes through a metabolic transformation. The glucose acquired from recent meals remains the primary energy source throughout the early hours of fasting. However, once this glucose is depleted, the body begins to draw on glycogen reserves stored in the liver and muscles. This initial transfer is simple and can often be completed with no obvious energy decreases.

2.2. 16/8 Fasting:

For novices, the 16/8 technique (16 hours of fasting followed by an 8-hour eating window) is generally recommended among the many IF regimens. Physiologically, it is a time frame that allows beginners to experience the transition from glucose to glycogen-driven energy without delving too deeply into fat metabolism or ketosis. It’s a modest introduction to the adaptive energy systems of the body.

2.3. Adaptive Challenges:

It’s worth noting that the principal difficulties that newcomers confront frequently revolve around the body’s ghrelin release – the hunger hormone. Even if the body has sufficient energy reserves, the regular meal schedule might cause ghrelin spikes, resulting in feelings of hunger. As one continues to practise intermittent fasting, the body adapts, and these hunger pangs may reduce or fit better with the selected fasting approach.

2.4. Benefits of a Gradual Approach:

Introducing intermittent fasting gradually rather than abruptly allows the body to progressively modify its hormonal and metabolic responses. This can reduce the likelihood of adverse symptoms such as extreme weariness, irritation, or light-headedness. From a physiological aspect, it’s a method of training the body, similar to gradually increasing intensity while starting a new exercise plan.

2.5. Frequency Considerations:

While the 16/8 approach specifies the period of fasting, the frequency (how many days per week IF is practised) does not. Starting with three to four days per week can provide a balance, allowing the body to adjust to this new eating pattern on fasting days while maintaining a sense of normalcy on non-fasting days.

3. Intermediate: Building Momentum:

3.1. Physiological Deepening:

By this stage, the individual’s body is usually more adept at switching between energy sources. The body’s reliance on glycogen stores becomes more obvious, and the body may experiment with deeper fat metabolism, particularly near the conclusion of fasting periods. This is when minor ketone synthesis may begin, indicating that the body is now obtaining energy from fat storage.

3.2. Alternate Day Fasting:

This strategy entails a day of ordinary calorie consumption followed by a day of severely reduced or even fully reduced intake. Physiologically, this on-off rhythm puts the body’s adaptive capacities to the test. Fasting days see an increase in fat metabolism as well as an increase in processes such as autophagy. The eating days, on the other hand, provide a break and allow for glycogen replenishment.

3.3. 5:2 Fasting:

This method calls for five days of usual eating followed by two days of significant caloric restriction (often 500-600 calories). Unlike the alternate day strategy, the two fasting days in the 5:2 approach are not always consecutive, allowing for greater flexibility. Physiologically, limited calorie days cause metabolic reactions similar to other fasting approaches but may be less intense than full fasts.

3.4. The Role of Hormones:

The hormonal benefits of intermittent fasting become more apparent at this point. There is a noticeable rise in norepinephrine production, which increases alertness and may aid in fat breakdown. Insulin sensitivity frequently improves, implying that the body requires less insulin to regulate blood sugar levels after meals. Furthermore, growth hormone release can be increased, which is important for tissue repair and muscle maintenance.

3.5. Adaptive Balance:

Achieving equilibrium is one of the most important physiological aspects to consider during this phase. While the body is being challenged more intensely than during the novice period, it is also critical to avoid pushing it to extremes. This entails being on the lookout for indicators of excessive stress, such as chronic exhaustion or prolonged spells of light-headedness.

4. More Intense Regimens: Deepening the Fast:

Indulging in more strenuous fasting regimens implies testing the body’s physiological limits. Individuals may desire to explore these deeper fasts as they move through their intermittent fasting journey in order to maximise possible benefits or push their metabolic flexibility.

4.1. The Warrior Diet:

Based on the ideas of ancient warrior tribes, this diet consists of a 4-hour eating window followed by a 20-hour fast. From a physiological standpoint, this technique prolongs the fasting response, increasing the body’s reliance on stored energy reserves. Because of the lengthier fast, there is a greater shift from glycogen to fat as the predominant energy source, with an increased risk of entering moderate ketosis, particularly near the conclusion of the fasting window.

4.2. Water Fasting:

Going beyond the normal intermittent fasting structure, water fasting includes abstaining from all caloric intake in favour of water alone. This is a physically demanding process. When glycogen reserves are depleted, the body dips deeper into fat reserves, resulting in increased ketone generation. This condition of ketosis denotes a metabolic adaption in which fat is converted into ketones and used as the principal fuel for cells, particularly brain cells, which cannot directly use fat as an energy source.

4.3. Physiological Benefits and Challenges:

Some of the generally mentioned benefits of intermittent fasting can be amplified by the depth of various fasting methods. Increased fat metabolism can help with weight loss, while increased autophagy may improve cellular health and rejuvenation. However, with these advantages come difficulties. Electrolyte abnormalities are possible, especially during prolonged water fasts. Monitoring hydration and, if necessary, electrolyte intake becomes critical.

4.4. Hormonal Responses:

Intense fasting regimes might cause significant hormonal alterations. There is an increase in growth hormone, which aids in tissue regeneration and muscle preservation. Insulin levels fall even further, which may aid people attempting to develop insulin sensitivity. Cortisol, the body’s principal stress hormone, may also fluctuate, which is important to monitor because sustained excessive levels might have negative health consequences.

4.5. Adapting and Listening:

In these longer fasts, the body’s feedback mechanisms become key guides. Extreme weariness, dizziness, or chronic irritation may indicate that changes are required. It’s also worth emphasising that, while short-term water fasts can be beneficial, longer fasts without professional supervision can be dangerous.

5. Pro Level: Extended Fasts and Specialized Techniques:

Individuals that engage in pro-level fasting are effectively pushing the limits of their body’s adaptive capacities. This level entails substantially longer fasting periods and specialised approaches that necessitate profound physiological adaptation, bringing possible benefits but also posing problems that must be carefully managed.

5.1. Prolonged Fasting:

Fasts that last more than 48 hours, often for several days, are called prolonged. The body depletes its glycogen supplies and depends primarily on fat storage over these extended periods. When fat is turned into ketones, it becomes the predominant source of energy. This severe ketosis may have therapeutic benefits, such as increased cellular autophagy and a potential metabolic reset.

5.2 Dry Fasting:

Dry fasting is one of the most rigorous forms of fasting, requiring complete abstinence from both food and water. Physiologically, this procedure puts a lot of strain on the body. Dehydration becomes a concern, resulting in decreased plasma volume, which can put cardiovascular and kidney systems at risk. Furthermore, the body begins to draw water from cells, potentially increasing fat metabolism because fat cells contain water that can be used.

5.3. Physiological Implications:

5.3.1. Metabolic Adaptations:

Extended fasts and specialised procedures cause a major metabolic shift. Aside from fat burning, the body may begin metabolising specific amino acids, however the presence of ketones aids in the preservation of muscle tissue to some extent.

5.3.2. Hormonal Fluctuations:

Fasting for an extended period of time might increase growth hormone output, which aids in tissue healing. There is also an increase in norepinephrine production, which supports alertness and energy as well as fat mobilisation.

5.3.3. Cellular Benefits:

The increased autophagic response during prolonged fasting may lead to improved cellular repair, the breakdown of old proteins, and even possible anti-cancer advantages.

5.4. Safety and Management:

Extended and specialised fasting regimens necessitate close monitoring and, in many cases, medical supervision. While the human body is extremely flexible, there is a narrow line between beneficial stress (hormesis) and potential injury.

It is critical to be cautious when refeeding after such fasts. In lengthy fasts, refeeding syndrome, which is characterised by electrolyte imbalance upon reintroducing food, can be a risk.

5.5. Who’s it For?

Pro-level fasting is not for everyone. Individuals with underlying health concerns, the elderly, or those with a history of eating disorders should proceed with caution. Such intensive programmes are generally best suited for experienced fasters willing to push their bodies to their limits and should be approached with caution and investigation.

6. Tailoring IF to Personal Goals:

Intermittent fasting (IF) is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Fasting affects our bodies differently depending on things such as heredity, metabolism, exercise level, and unique health concerns. As a result, adjusting IF to personal goals is critical.

6.1. Metabolic and Weight Goals:

For people looking to lose weight or improve metabolic flexibility, IF can help with the transition between carbohydrate and fat metabolism. Those looking to lose weight may prefer longer fasting windows or more frequent fasting days to supplement their calorie deficit.

6.2. Cellular Health and Longevity:

Autophagy, the body’s cellular “cleanup” system, can be boosted by prolonged fasting. Individuals interested in cellular health or potential longevity benefits may find this fascinating.

6.3. Hormonal Balance:

Certain fasting regimens may be more beneficial to hormonal health. Shorter fasts, for example, may be preferable for women concerned about potential hormonal swings or those suffering from diseases such as PCOS.

6.4. Athletic and Fitness Goals:

Athletes or fitness fanatics may customise IF to aid with muscle maintenance or growth. Consuming protein-rich meals during eating windows or timing feedings to coincide with workouts can help to maximise muscle protein synthesis.

6.5. Lifestyle and Well-being:

Beyond the physical, a person’s fasting technique of choice can correspond with their daily routine, sleep patterns, and even social engagements, guaranteeing a sustainable and joyful fasting journey.

7. Safety Considerations:

When practising IF, as with any big dietary change, safety must come first. It is critical to understand the physiological responses and associated hazards.

7.1. Recognizing Extremes:

Extended fasting, especially when not well prepared, might result in problems such as refeeding syndrome. This condition occurs when reintroducing food after a protracted fast, resulting in potentially serious electrolyte imbalances.

7.2. Monitoring Hydration and Electrolytes:

It is critical to stay hydrated during fasting, especially for longer periods of time. Additionally, persons on extended fasts may need to ensure electrolyte balance through supplements or specialised foods during eating windows.

7.3. Understanding Hormonal Fluctuations:

While IF might have beneficial hormonal benefits such as enhanced growth hormone release, it may also cause an increase in cortisol, the stress hormone. Prolonged high cortisol levels can have a variety of negative effects, ranging from sleep disruption to immune system suppression.

7.4. Potential Nutrient Deficiencies:

Relying entirely on shorter eating periods can make it difficult to obtain all vital nutrients. During eating periods, it is critical to focus on nutrient-dense foods and consider supplementation if necessary.

7.5. Special Populations:

Pregnant or breastfeeding women, those with a history of eating problems, or anyone with specific medical conditions should use IF with caution or under the supervision of a healthcare practitioner.

7.6. Adaptive Symptoms vs. Warning Signs:

While modest fatigue, initial hunger pangs, or even a slight headache may be part of the body’s adaptation to IF, persistent or severe symptoms should not be overlooked. Dizziness, extended irritability, fainting spells, or serious gastrointestinal disorders necessitate a re-evaluation of the fasting strategy or consultation with a healthcare practitioner.

Frequently Asked Questions

u003cstrongu003eHow often should beginners practice intermittent fasting?u003c/strongu003e

Beginners should start gradually. A good approach is the 12/12 method (12 hours fasting, 12 hours eating), practiced 3-4 times a week. This allows the body to adapt without causing significant stress or discomfort.

u003cstrongu003eCan I do intermittent fasting every day?u003c/strongu003e

Yes, you can practice intermittent fasting daily, especially as you become more accustomed to it. Methods like the 16/8 are suitable for daily practice. However, listen to your body’s cues and take breaks if needed.

u003cstrongu003eIs it safe to do prolonged fasting regularly?u003c/strongu003e

Prolonged fasting, such as fasts over 48 hours, should be approached with caution and generally not done frequently. For most people, doing prolonged fasts more often than once a week can be excessive. Always consult with a healthcare professional before attempting prolonged fasts.

u003cstrongu003eWhat is the best intermittent fasting method for advanced fasters?u003c/strongu003e

Advanced fasters often benefit from more rigorous methods like the Warrior Diet (20-hour fast) or alternate-day fasting. These approaches deepen the fasting state, allowing for greater metabolic and cellular benefits.

u003cstrongu003eHow can I choose the right fasting frequency for my fitness goals?u003c/strongu003e

Align your fasting method with your fitness routine. If you’re into high-intensity workouts, consider shorter fasts or time your eating window around your workout times for energy. Extended fasts might be more suitable for those focusing on weight loss or metabolic health.